NOTES ON A RITUAL FOR THOSE LOST AT SEA

I.

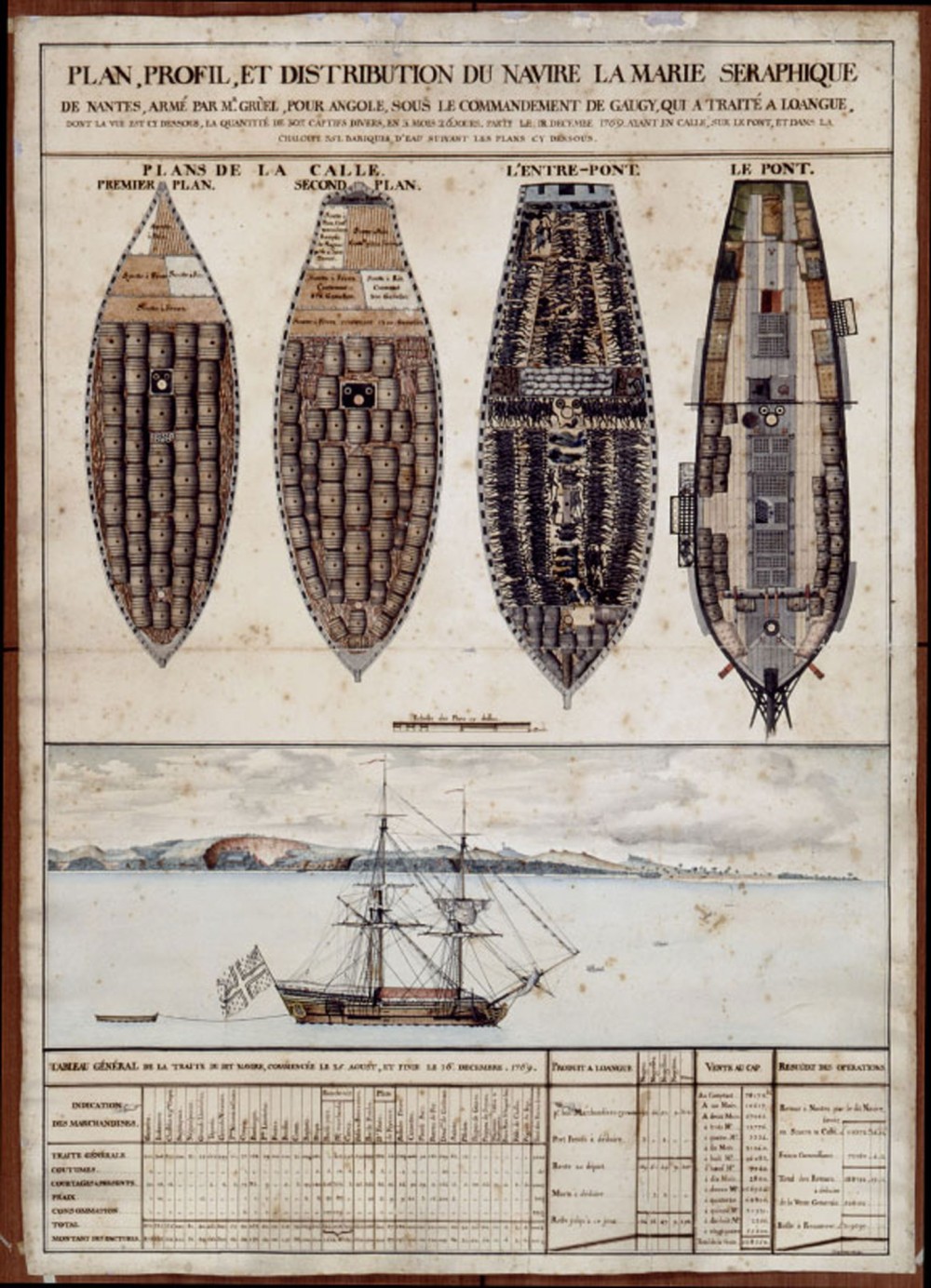

Paul Gilroy wrote The Black Atlantic in 1993. In it, he outlines a culture born in the Atlantic Ocean, spreading beyond the ports surrounding it. He examines modernity from this fluid space, devoid of solid ground yet deeply rooted in its watery territory.

II.

From the Créac’h Semaphore, the Atlantic always seems black to me…

III.

Does this liquid, ever-changing body remember the flesh and bone bodies it once held?

An intuition: the salt carries remnants of this fluid memory.

I sculpt this material and learn that salt harbors a slow, corrosive rage: every tool rusts at its touch.

It draws moisture from bodies, settles as fine dust, and gradually eats away at its surface.

IV.

I seek traces of life born from death—the Drexciyans or other yet-to-be-identified beings.

V.

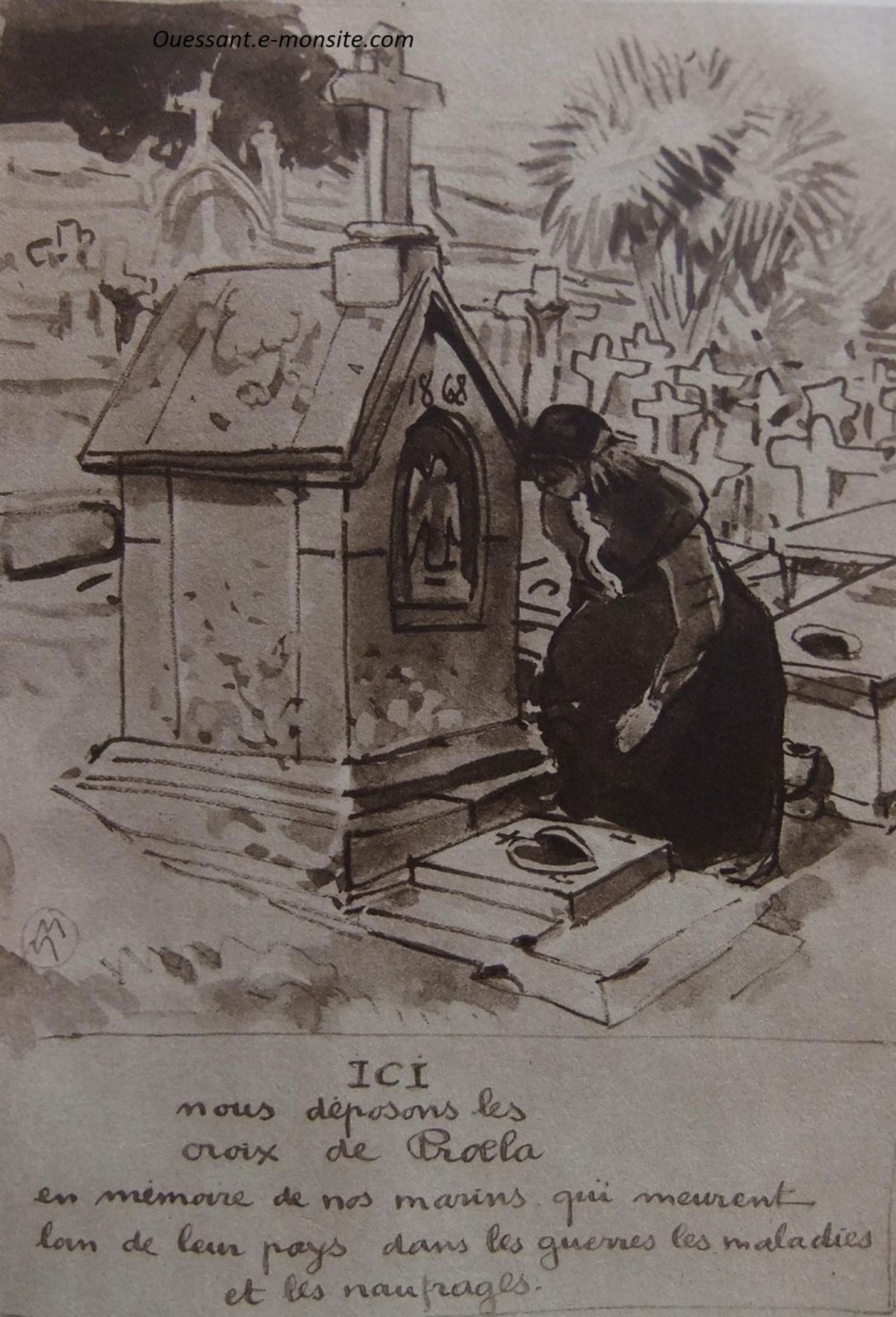

The cemetery in Lampaul contains a modest oratory that once received wax crosses. In the absence of bodies, wax bore witness to those lost at sea.

The town hall and the church learned of the disappearance before the family. The priest would give a small wax cross, called proëlla, to a relative of the deceased. The cross was brought at night, when the family of the lost person was gathered. This was followed by a ritual at the church, where the cross was placed in an urn alongside others lost during the year.

VI.

On May 29, 1764, Jean Mor, servant to Claude César de Nortz, was hanged and then burned in Saint-Louis Square in Brest.

His ashes were scattered to the four winds.

Did some of them reach the Atlantic—the same ocean that might have brought him from Martinique to France in servitude?

The freedom promised to the 20-year-old man was never given. Using poison made from the bois-piment plant, he tried to claim it himself. Three attempts, none successful. Tortured, forced confessions, forgiving God, society, and the king. Death.

His story echoes another in New France. Separated from Jean Mor by thirty years and the breadth of the Atlantic, Marie-Josèphe-Angélique, born in Portugal, died in Montreal in 1734. She was tortured and burned after being accused of setting fire to her owner’s house. Part of the town burned afterward. Her ashes, too, carried by the winds, may have found their way to the Atlantic—this underwater cemetery.

A street in Brest bears Jean’s name, and a park in Montreal honors Marie-Josèphe-Angélique. These are not witnesses but clues.