Elvan Zabunyan

Résidency semaphore #21

A retreat residency, connected to the context of the Créac’h lighthouse on Ouessant.

Ouessant - sémaphore du Créac'h

Résidency semaphore #21

A retreat residency, connected to the context of the Créac’h lighthouse on Ouessant.

Announcing a stay in Ouessant to one’s circle sparks vivid reactions: warnings, thoughtful advice, exclamations of joy, and curious glances. People speak of the waves, the wind, the light that shifts in seconds, the sheep, the emptiness, the landscapes. Upon arrival, what one discovers is a timeless and age-old constancy—a connection to time that unfolds moment by moment. A rapid addiction to this unique atmosphere takes hold, and settling into the Créac’h semaphore makes the experience even more singular. Unprepared, the imagination runs wild. Climbing immediately to the watch room, the view of the ocean unfolds: the crashing sea, the rocks standing defiantly against it—all there as a living panorama, captivating from morning to late into the night.

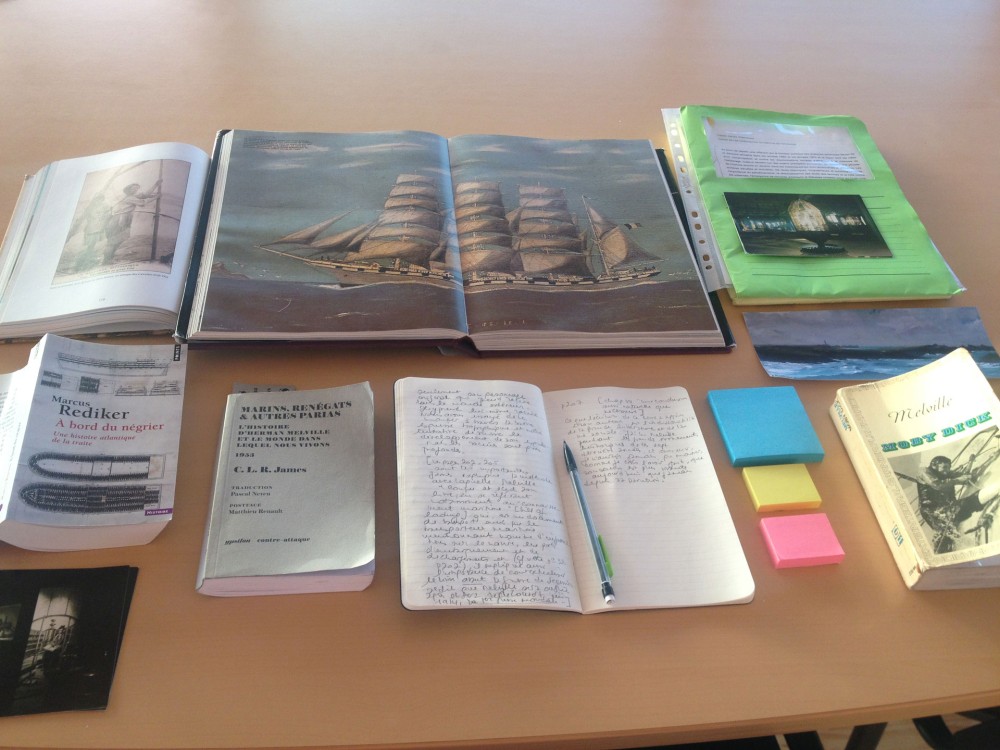

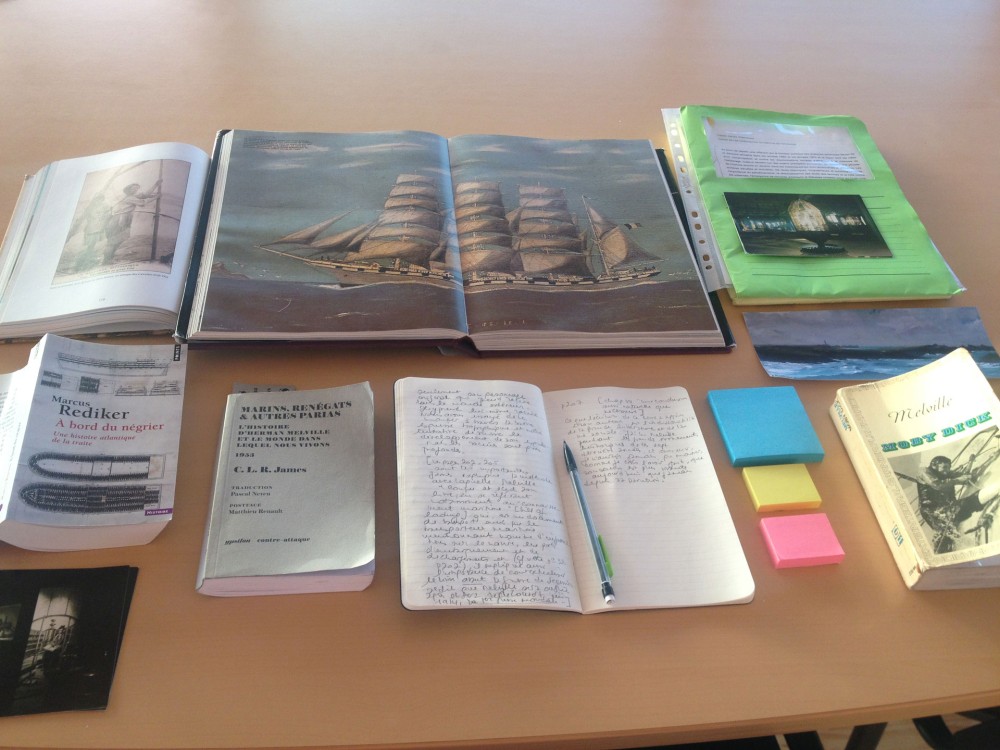

Books are laid out on the table, as coming to Ouessant in January 2018 for research is a choice to confront ideas, introspection, and contemplation with a study of the memory of slavery through contemporary arts. Here, specifically, the focus is on forms created by painters, filmmakers, and writers as they imagined, through images, sounds, and words, the violence of the journey between Africa and the Americas. This Middle Passage, where the Atlantic served for centuries as the path for the most brutal transformations in human history and the tomb of thousands upon thousands of African captives—cast overboard or leaping to escape the cruelty of enslaved destinies.

In 1993, Patrick Chamoiseau spoke with Édouard Glissant in Martinique, where Chamoiseau reflected on the experience of the voyage and the slave ship hold. Glissant responded by referencing the first chapter of his book Poetics of Relation (1990), titled The Open Boat: “It represents the abyssal experience for our communities—the abyss of the ship’s hold and the sea into which both the dead and sometimes the living were cast, with cannonballs chained to their feet. And this experience of the double abyss, of ship and sea, also becomes that of the unknown, terrifying abyss. It means heading toward something entirely unknown, without history, without geography…” For Glissant, this abyss defines the experience of Caribbean peoples.

On Ouessant, one can buy a tourist map of shipwrecks, marked with their “authentic positions,” showing the island alongside locations where vessels were swallowed by the waves, victims of mist, wind, and reefs that made landfall treacherous. Ouessant’s history is tied to these disappearances, to the underwater souls navigating its imagination and beliefs. These friendly ghosts also allow African memories to weave through the waters, casting light with every spray of the sea, illuminating waves, conversing with the sun’s rays, and reaching the beams piercing the clouds. Such intense connections to nature are only possible because the air carries more than majestic scenery—it holds traces of the abyss transcended through the grace and intellect of artists and writers who gave it diverse forms of expression.

Among the books on the worktable, layered in resonant references: Moby Dick (1851) by Herman Melville, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (1953) by C.L.R. James, The Slave Ship: A Human History (2008) by Marcus Rediker, as well as excerpts from The Sea (1861) by Jules Michelet, whose work James read. In the introductory chapter “The Sea Seen from the Shore,” Michelet shares his thoughts:

“Water, for all terrestrial beings, is the unbreathable element, the element of asphyxiation. A fatal, eternal barrier irreversibly separating two worlds. It’s no surprise that the vast body of water called the sea, unknown and shadowy in its depths, has always loomed as a terror to human imagination. To the Easterners, it is the bitter gulf, the night of the abyss.”

A few pages later, Michelet writes:

“If one dives deep enough into the sea, light soon fades; one enters a twilight where only a sinister red persists, until even that disappears into complete darkness, absolute obscurity save for perhaps some frightful bursts of phosphorescence.”

Michelet’s descriptions draw from the writings of Matthew Fontaine Maury (1806–1873), a pioneer of hydrography. Michelet’s “bitter gulf” aligns with Glissant’s “abyssal experience,” rooted in the tragic narrative recounted by Rediker. Rediker speaks of African sharks adapting to American waters during voyages alongside slave ships, feeding on the bodies of captives cast into the ocean’s expanse. The chromatic elements Michelet describes—“sinister red,” “absolute darkness”—color the violence of slavery, the largest system of globalized capitalist exploitation in history.

The brutality inflicted on enslaved people during the Middle Passage unfolds page by page. Looking up from books and notes, one gazes through the watch room windows: clouds race by, the sky attempts to touch the sea but is repelled by waves and foam, white at dawn, pink at sunset. The Atlantic stretches out, the very ocean that transported nearly 15 million enslaved people in chains over four centuries.

Night falls; vision gives way to sound—the deep, unrelenting resonance of the waves, the ocean’s physical and acoustic presence. Ouessant enables this experience. Leaving the worktable, one climbs a few steps to the semaphore terrace overlooking the landscape. The strangely milky, crystalline light of the lighthouse soothes, resting on the waves, illuminating them for fleeting seconds before retreating and returning. On the terrace, the wind destabilizes; one staggers forward, leans in, and watches the Créac’h optical system gleaming like a diamond.

Thanks to Ouessant’s timeless atmosphere, the reflections undertaken during this stay opened up a new perception of the sea in relation to history—its history, that of African and American slavery. For C.L.R. James, his book on Moby Dick interrogates the past to understand the present. Immersing oneself in this proposition, research continues in this vein.

Walking on Ouessant’s thick, green grass carpeting the island’s rocky terrain feels like stepping on the back of a prehistoric creature—both soft and dense. Off the beaten paths, one is drawn to a narrative where the vast brutality of slavery clashes with intellectual engagement and the freedom of artistic imagination. One bends but does not break. Pressing forward against the wind, breathing the iodized air, benevolent spirits flutter in the atmosphere, accompanying each step.

*Elvan Zabunyan