Laurent Tixador

Semaphore Residency #19

A retreat residency, connected to the context of the Créac’h lighthouse on Ouessant.

Ouessant - sémaphore du Créac'h

Semaphore Residency #19

A retreat residency, connected to the context of the Créac’h lighthouse on Ouessant.

Organizing a manhunt, embarking on a glacier expedition, crafting an electrical power strip from beach debris, unearthing a Franco-Soviet rocket… these are just a few of the actions, performances, and experiments that define Laurent Tixador’s work.

Challenging ideas of ecology, communal living, recycling, survival economies, and modes of production, the artist (born in 1965 in Colmar, France) continuously seeks and creates unusual situations, aiming to provoke diverse opportunities and discoveries.

John Cornu: “If we compare what each of us expects from life, we must distinguish between the one who is content with moderate success, hitting close-range targets, and the one who, however low and fruitless his life may be, keeps aiming higher, though his acute angle of vision scarcely rises above the horizon.” Henry David Thoreau wrote this in Life Without Principle. I first met you in Siberia and—unless I’m mistaken—discovered an artist who acts upon his ideas. By this, I mean you seem to adhere to a philosophy, particularly in relation to ecology. How do you position yourself regarding Thoreau’s distinction, and how do you perceive his philosophy? I’d also like you to introduce the piece Walden, which will be on display at the gallery. My question is broad, but I’m genuinely curious about how, as an artist, you articulate the relationship between ecological ideology and its materialization.

Laurent Tixador: My approach closely aligns with what Thoreau developed in Walden in that I’ve almost never invested financially in creating a work. I don’t buy materials, I don’t have a studio, and every object I produce is made manually by me. It’s a way of demonstrating that one can step away from the traditional economic system, disrupt it by disregarding it. I work exclusively with recovered materials to promote their use. It’s cost-free, but it requires adaptation. That’s where it becomes interesting because every new resource discovery comes with unique properties, which in turn inspire new creations. This process becomes a collaboration between the material and me, as I’m no longer the sole decision-maker.

From this premise, I began using materials that don’t belong in their environment, integrating pollution cleanup into my artistic practice. Walden was one of the first pieces I made with this intention. During a journey on foot from Nantes to the Belleville Biennale (Paris) in September 2014, I pledged to create works for the exhibition along the way. Walking along departmental roads, I encountered countless discarded and crushed packaging items, half of them from McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and Nestlé. It was disheartening. I collected a large amount, placing some in trash bins and using others to document a sort of journal. This saved paper and gave purpose to my walk. Turning over the packaging, I noticed the “M” of McDonald’s transformed into a “W,” instantly reminding me of Walden.

On my return, this became a multiple comprising a collected cup and a stencil. Buyers of this multiple can reuse the stencil as often as they wish, thus continuing the act of cleanup indefinitely. The work becomes an expansive, collaborative effort.

JC: It’s evident that material recovery, even of waste, is central to your practice. This is apparent in Multriprise, a project stemming from a productive residency on Ouessant Island facilitated by Marcel Dinahet. Can you tell us more about this?

LT: Ouessant is an island historically devoid of trees because of its strong winds. Collecting driftwood from beaches was a traditional practice, as it was the only source of material for building. All the old houses’ beams and furniture were made from it. More recently, a shipping lane passing offshore caused cargo containers to be lost at sea, leading to unusual debris washing ashore—celluloid ducks, sneakers, and more—delighting beachcombers. Although the lane has been redirected, the interest in collecting remains strong among many locals. Nowadays, there’s more fishing net and plastic waste dumped overboard than treasures. This is true for all coasts, and I find it just as criminal to ignore such waste as to dump it. Cleaning up is satisfying and can be enjoyable, but more importantly, it replaces consumption with an act of creation. Repairing, finding ingenious solutions, and recycling chance finds can be deeply rewarding.

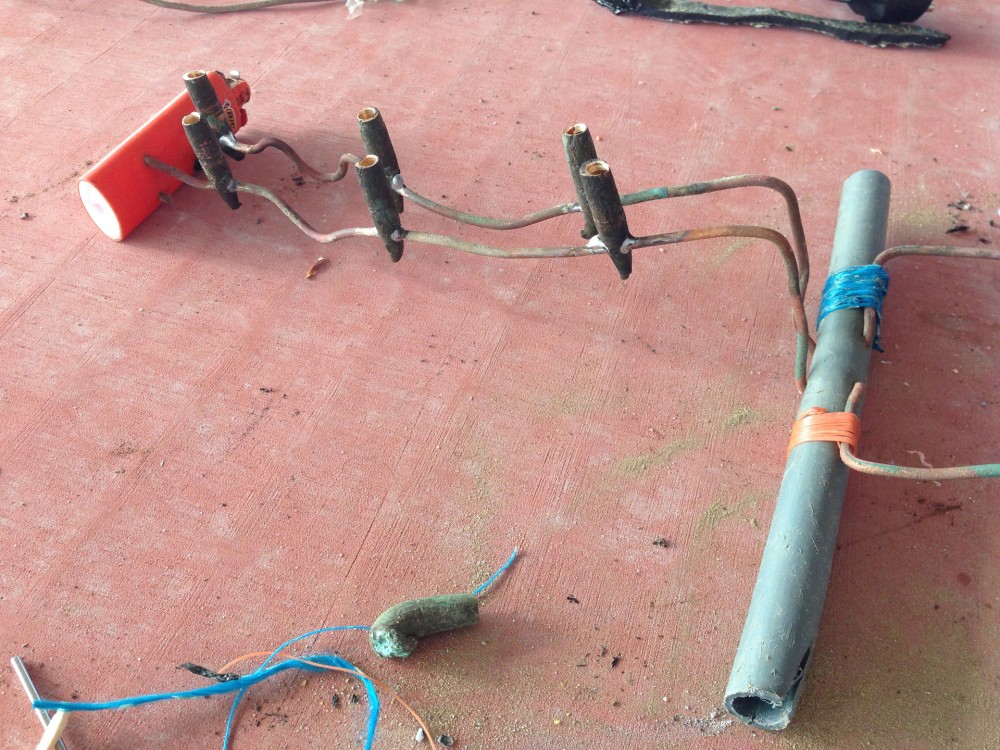

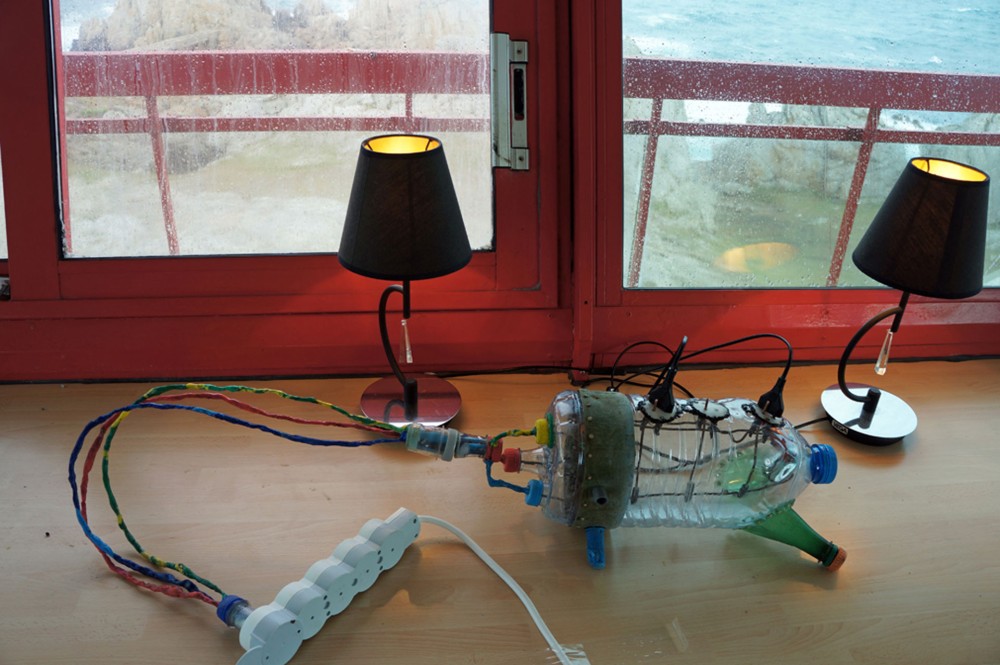

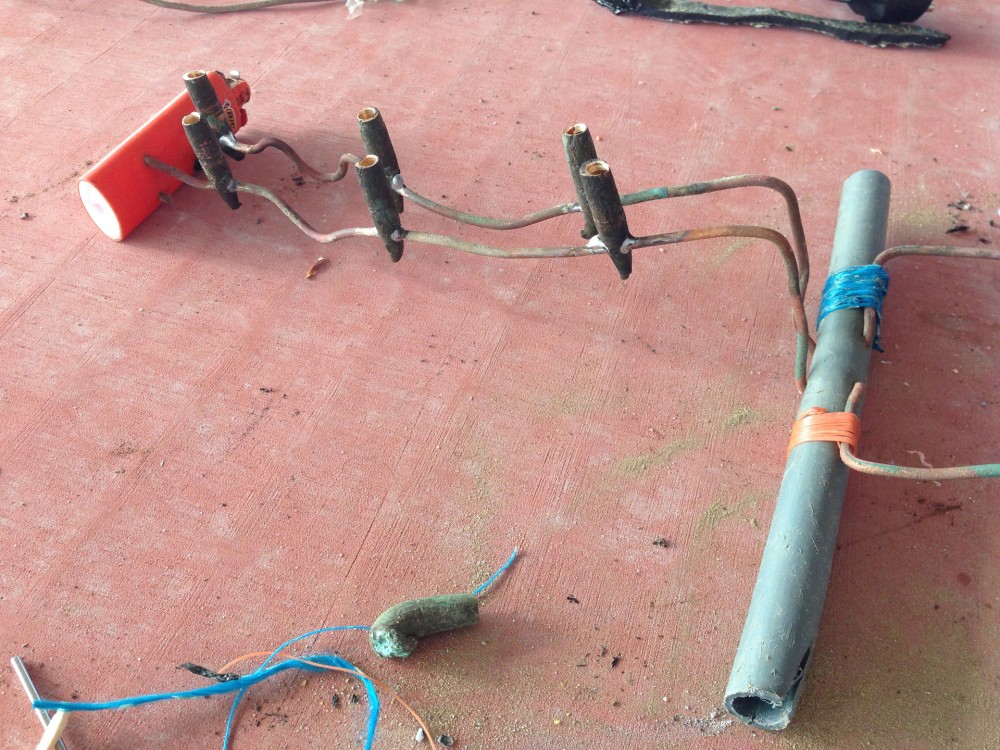

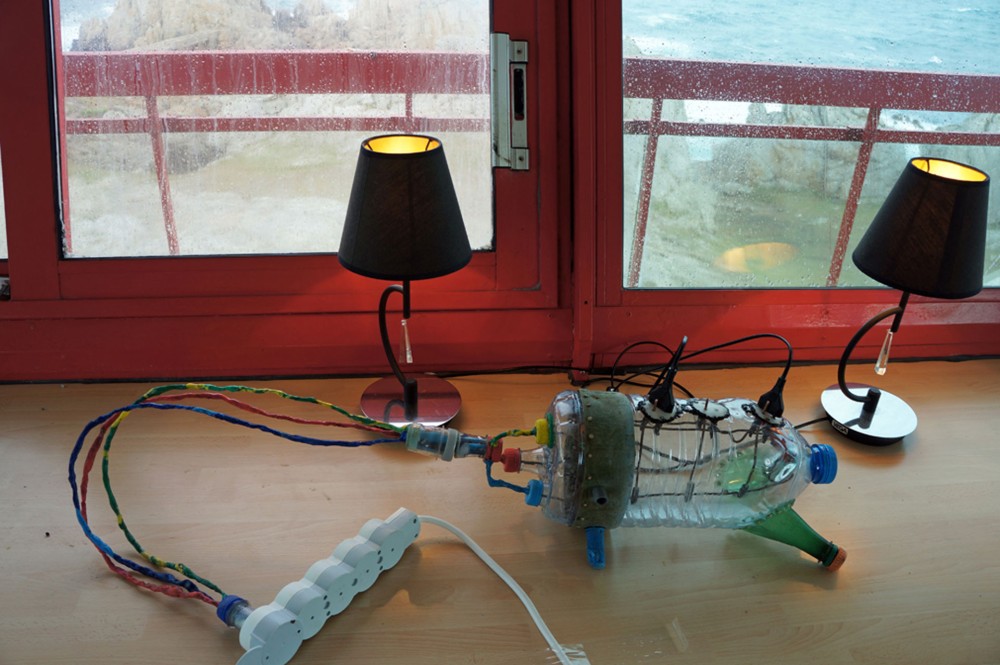

There’s a Hindi term for this mindset: jugaad. It refers to transforming constraints into opportunities with flexibility and simplicity. On Ouessant, I systematically collected every piece of plastic waste I saw to prevent it from returning to the sea. From this collection, I extracted the materials needed to make a power strip, a system I’m familiar with. To assemble it, I repurposed old bullets found at a 20th-century shooting range as connectors for copper wire, insulating them with softened plastic bottle caps—red and blue for live and neutral wires, yellow and green for grounding. I used longline fishing wire for mechanical fastenings and tar scraped off rocks as adhesive. The final object contains nothing but materials collected from the beaches.

Previously, during a stay on the Kerguelen Islands, I had cleaned up the remnants of a weather rocket from the 1970s Franco-Soviet Intercosmos program, which studied the upper atmosphere. The rocket’s remains, a pollutant in a natural reserve, deserved to be moved to a space where its historical value could be appreciated. With colleagues from the Port-aux-Français base, we excavated the debris and carried it back on a stretcher over a three-hour hike. Ecology, to me, is about putting things where they belong.

JC: You’ve just returned from a glacier expedition in Switzerland. Can you describe the trip and the painting project it inspired? Additionally, how do you approach creativity: do you start with an idea and realize it, or does experimentation lead you to develop specific projects?

LT: Visiting a glacier is about seeking untouched landscapes, free from civilization. It’s a dangerous, earned experience. Such spaces, where one can go without paying, are rare and are the ones I seek as studios—sites brimming with unforeseen influences and new resources.

On the Aletsch Glacier, I was struck by significant deposits of soot particles—fine airborne carbon from vehicle exhaust and heating systems. Their black color absorbs sunlight, accelerating the glacier’s melting. I had seen this phenomenon before, even as far as the Greenland Ice Sheet. These particles condense into greasy, odoriferous black granules. I painstakingly scraped as much as I could to “save” the glacier and kept a kilogram to make pigment.

Though I’d never painted before and would have preferred not to start for this reason, I felt it better for these particles to end up visible on a wall than on the mountains. This exhibition consists entirely of refuse.

Henry David Thoreau, Life Without Principle, Mille et une nuits Editions, Barcelona, 2008, pp. 17–18.

Interview conducted on the occasion of the exhibition “Trasher” by Laurent Tixador, at Galerie Art & Essai – Université Rennes 2, from September 28 to November 10, 2017.

www.espaceartetessai.com