Simon Faithfull

Semaphore Residency #30

Retreat residency, linked to the context of the Créac’h semaphore in Ouessant.

Ouessant - sémaphore du Créac'h

Semaphore Residency #30

Retreat residency, linked to the context of the Créac’h semaphore in Ouessant.

The deep, resonant rustling of a wave crashing against the granite is a sensation that you feel deep within your being. The most pounding techno from a Berlin nightclub doesn’t have a resonance chamber as powerful as that of the cliffs of Ouessant. Eight times a minute, a dazzling wall of wild water crashes against the combative rock. The moment of impact is not so much a sound as a visceral shock that pierces you. As I write these lines, with the ocean all around me, the wind from yesterday, which made my tower tremble all night, still echoes in the choppy sea. The waves crashing against the rocks below beat a hyper-slow, hyper-heavy dub track from the depths. These are scores that avoid the rhythmic signatures of human-created music and slow them down to the rhythm of the ocean: 8 B.P.M. (eight beats per minute). It’s the soundtrack of a liquid planet. It turns out that the heavenly music of the spheres does not sound like a harpsichord; it creaks and pounds in a sub-audible low tone that resonates deep inside.

My new home, for a month, is a granite block located twenty kilometers from the tip of Brittany, at the far west of France. The island of Ouessant rises from the swells of the Atlantic – confusing its currents and forcing them to churn around its jagged borders. A residence in a semaphore, at the foot of the Créac’h lighthouse – perched at the edge of Europe, in the middle of the wild ocean. Finis Terrae: “the end of the earth.” This semaphore was built by the navy on the cliffs of the island’s Atlantic coast. It was created to monitor the ships still passing through the swells of the ocean and to send them signals with its flags and pulleys now corroding on its roof. The technology of a global power that watches over its merchant ships and naval forces.

My temporary home looks like the control tower of an airport or, better yet, the bridge of a container ship. On the top floor, where I work, half-circle windows, angled 45 degrees toward the front, open onto the ocean that surrounds me on three sides. The center of this ensemble faces directly west – toward the setting sun and the clouds approaching. Weather fronts appear above the liquid horizon, and curtains of rain move toward me, sweeping across an empty scene and rushing onto the waves until they splash against the glass. Then light silver streaks, like scratches along the dark horizon, slowly glide toward me, turning into pools of sunlight shimmering on the gray water. In turn, these patches of light rush toward me through the swells. It’s a constantly renewing weather spectacle. Fleeting moments that break, each in its signal, across thousands of kilometers of free water.

From the bridge of my ship, hypnotized by the waves and fleeting light, I feel as though the semaphore, and the island of Ouessant as a whole, are moving forward, cost what may, against the constant movements of the elements, like a granite ship setting sail. But, in fact, we are the only static things. Everything else seems to be in constant motion. Oscillations of energy from forgotten storms rush toward me through the Earth’s liquid skin. Winds, perhaps somewhere near the Azores or the Bahamas, torment the trembling envelope of a vast liquid entity. Resonating frequencies, troughs, and peaks, carried around the planet to meet the granite of Ouessant. Monotonous rhythms transform into piles of foamy water that crash against the first immovable object since the American coasts.

If a body plunges from a rock into the water, it slides, smoothly, into the flickering blue – the cold lips of the water closing over its vanishing heels. But if a body falls from a height of more than thirty meters, due to the speed of impact, it feels as though it’s falling onto a concrete parking lot. Eight times a minute, an accelerating mass of water strikes a static rock.

Then comes an invisible wave, slower. The moon pulls a mass of ocean and our rotating liquid planet crushes a mound on the other side of the Earth. We complete a revolution once a day within these two bulges, and so, twice a day, the water rises and extends to the rocky coves of the island. Today, in Ouessant, the waters have risen by seven meters. If, at 1 p.m., I stood on a rock at the water’s edge, by 7 p.m., my head would be more than five meters below the sea’s surface. The violent currents surrounding this island twist over the rocks and slip into the crevices – hurrying to fill the bays and float the small boats once more.

This part of the island is mainly populated by rocks, lighthouses, and sheep. The hamlets of Ouessant are clustered in steep, sheltered bays on the other side of the island, toward the hidden continent and the small ferry that appears three times a day. The low stone farms are scattered a little further, in a treeless landscape, but they too nestle in crevices among the wandering sheep.

My only neighbors are the black-and-white striped lighthouse and the chaotic piles of granite rising on spongy mats of tufts of grass and purple heather. At the water’s edge, these piles push into the violent waves in rows of jagged teeth. At dusk, the granite needles tower over the bare landscape, forming strange shapes, twisted by wind and waves. When the sky darkens, the lighthouse beams begin to turn. When I lean over the balcony of my tower, the eight beams of light extend above my head into the darkness of the ocean, scanning the horizon. The swirling crown of light rays radiates through the drizzle and illuminates eight slices of mist and swirling rain. A silent nightclub just for me. During my sleep, I feel my neighbor behind the curtains keeping an eye (or four) on me throughout the dark night.

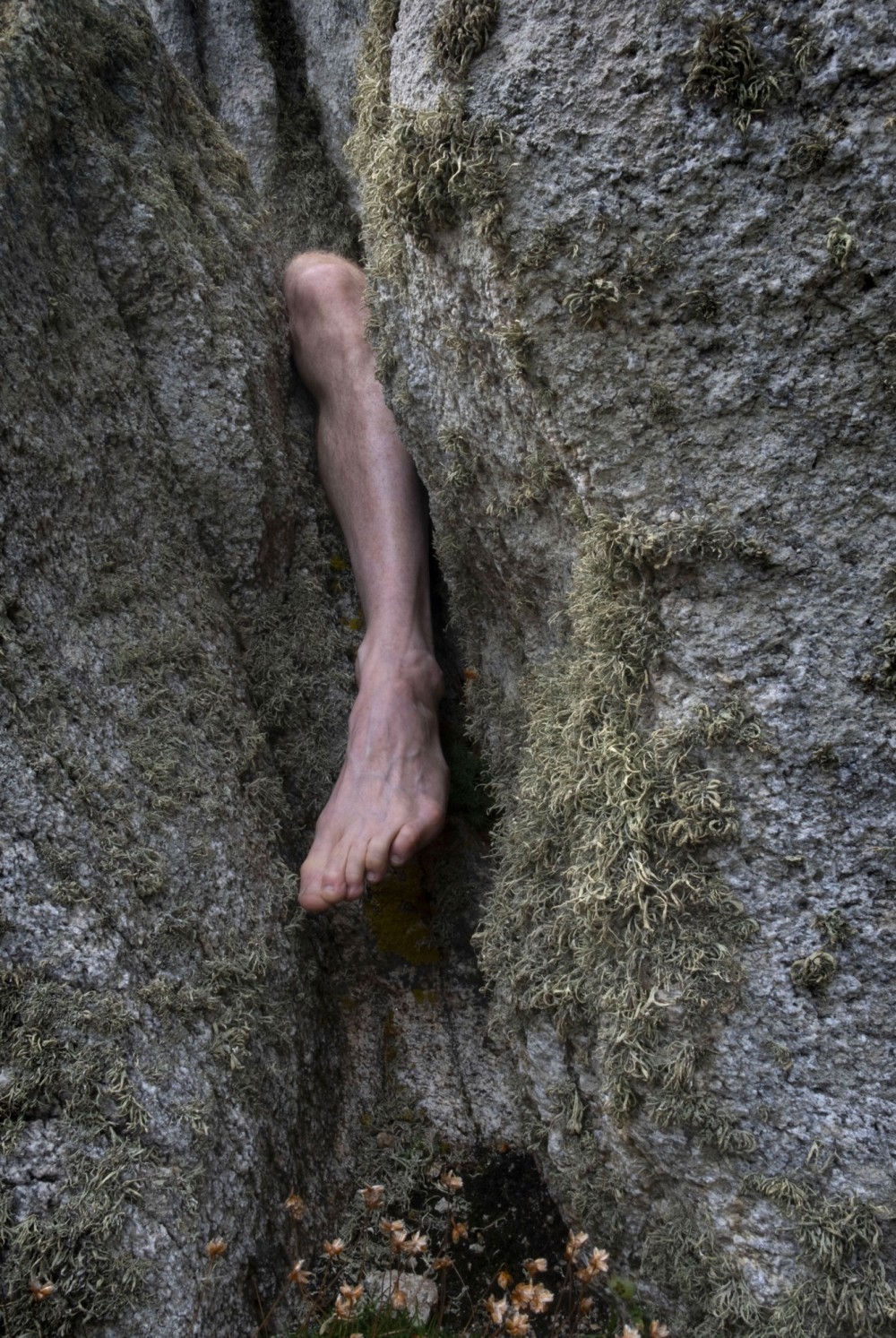

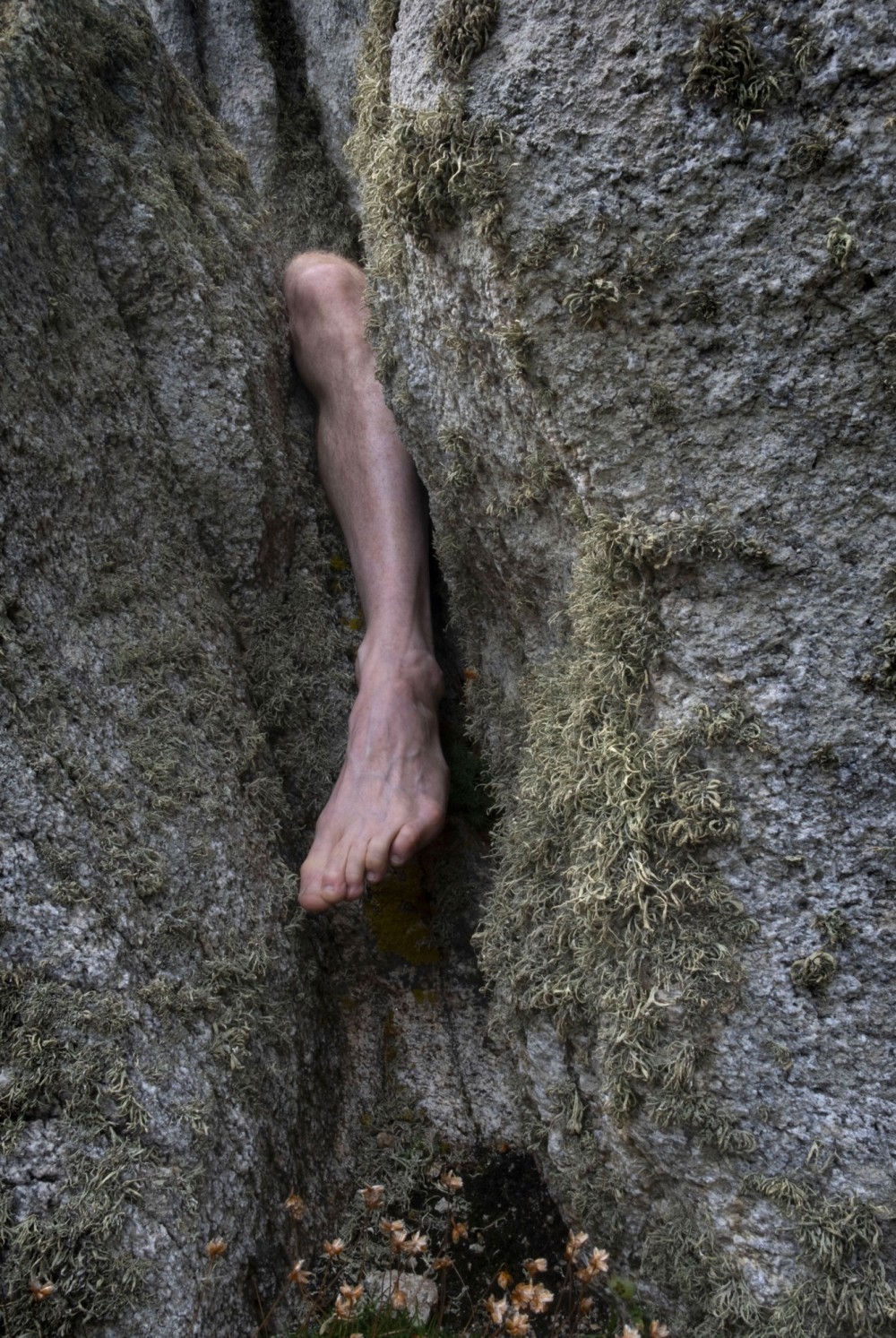

Every stone on this island slowly becomes covered in fur. The lichens, which find their way millimeter by millimeter across the curves of the huge rocks and granite piles, also infiltrate the window lintels and the statues in the island cemetery. One of Jesus’ eyes slowly closes beneath the green veining and mutant fronds. An entire menagerie of ancient organisms creates a velvety coating of deep orange and delicate greens or spreads like bruises of gray and black. In the crevices of the rock walls and reefs, like teenagers, hairs grow: the fuzz extends slowly, covering their curves.

I climb up to an abandoned building, the foghorn station, built next to the lighthouse on the tip of one of the high granite piles. Its rusty, empty portholes overlook the ocean that crashes against the stone below. With this dizzying view, you might feel as if you are in the space station from Stanislas Lem’s novel Solaris. A corroded version of Lem’s space laboratory watching the surface of an alien liquid world – a sentient ocean striving to understand the time scale and narrow mind of the human being stirring above it. The sea grinds the rock and corrodes this tower from another planet, reducing it to its salty and ferrous elements. The smell of crumbling rust and sticky salt.

Although these rocks are made of sharp igneous granite, coming from the bowels of the Earth, they have taken, near my tower, strange and sensual forms – softened by the passage of time and their velvety lichen skins. In the mist and errant spray of the ocean, they seem like massive stone bodies breathing to the rhythm of millennia. The undulating folds of some of these rock walls resemble stone brains, with slow and deep thoughts anchored in geological time, while an annoying fruit fly trots across them.

The wind scratches me as I descend. My eyes water: small streams snake down my cheeks. The salt of my tears is a memory of the ocean, from which we all – terrestrial creatures – came.

In a secluded cove, protected from the waves, a dark shape sways in the swells. The head of a seal. Impossible to distinguish it from a fishing buoy. It then dives back beneath the water’s surface. Another head, closer, or perhaps the same seal, watches me. It throws its head back and yawns a long yawn of boredom. With all its fat, it seems to float effortlessly. Its head emerges, its nose pointing and twitching above the water.

As I awkwardly make my way through the rocks, I try to blend into this environment. I manage to win the battle I’m fighting with my reptilian brain by overcoming its resistance to the cold and the unknown. I leap, through a flickering mirror, into another reality. The water envelops my torso: fifteen degrees of cold and shock. My entire body rushes to react to my skin’s screaming. My diaphragm contracts, drawing a large breath into my lungs. Reflexively, my blood pulls away from the surface, radiating its warmth deep inside me. But gradually, my body accepts the embrace of the water, relaxing into this new floating world. My breath slows. I glide, descending through a silent garden of undulating kelp. The urgent pain transforms into a firework of tingling sensations that sparkle on my skin as I dive into a weightless forest.

According to a controversial theory, humans descend from semi-aquatic primates. Hairless monkeys who lived by paddling in the fertile waters of ancient bays; they gradually became bipedal as they struggled to keep their heads above the water. This theory explains why our babies are born coated in a waxy substance, like seal pups, because our ancestors were born in salty water. The reason we can hold our breath (unlike most mammals) and why our kidneys can expel salt efficiently is because the ocean is our origin.

Its dark, liquid eyes blink at me above the waves. I wonder why seals returned to the water. Why they left our adventure and stopped crawling on solid ground. Why they abandoned our fight against gravity to slip their bodies into the water that carries us. Shedding their limbs, relaxing their necks. Perhaps they decided that it was enough – that they never wanted to have a dry throat or dry eyes again. That they never wanted to feel the urgency of thirst. Seals and whales decided to return to the fish. To rejoin the amniotic fluid of the ocean. But it was too late. The bear-like creature that fell back into the sea had already lost its ability to breathe water. Seals can only masquerade (magnificently) as fish for the length of a long breath. But they must finally come up to the surface to fill their lungs or give birth to their young. Whales have further refined their transforming act by becoming masters in the art of raising their air-breathing babies entirely in the ocean. Mammalian milk swirls in the salty waters, while their whale calves nurse in the depths.

Its head disappears again beneath the surface.

Seen from space, the Earth appears as smooth and silent as a glass ball suspended in the infinite darkness – a gleaming arc of sunlight on its blue surface. But below, amid the bubbling kelp, it is difficult to imagine the calm of space. In the midst of complexity and noise, in the frenzied and slimy confusion of life, it’s hard to recall the definitive contours of this soft bubble. I’ve drunk my fill of the ocean, become enamored of fuzzy stones, and realigned myself with the deep tides of our world. I think I would like to be a seal. To surrender. To end this adventure with solid ground and slip once more under these waves.

Simon Faithfull

his text was written by Simon Faithfull during a residency on the island of Ouessant, organized by ‘Finis terrae – Centre d’art insulaire’ (www.finis-terrae.fr). It is published here as part of the exhibition Cette mer qui nous entoure conceived by artconnexion (www.artconnexion.org) at the invitation of Espace Le Carré, Espace Municipal d’Art Contemporain, within the framework of the Utopia edition of lille3000.

Production: artconnexion

Translation: Marie Ollivier-Caudray

Proofreading: Stéphanie Quillon

Graphic Design by Simon Faithfull (www.simonfaithfull.org) & Eggers+Diaper (www.eggers-diaper.com)

Printing May 2022 – University of Lille

The works and text produced during the residency are presented in the exhibition Simon Faithfull - 8 B.P.M. (experiments with time) at Galerie Polaris in Paris, from March 11 to April 15, 2023.