Grégory Jérôme

Residency tempest #7

A residency that shifts perspectives, set in an isolated territory swept by winds and waves.

Ledenez Vraz

Residency tempest #7

A residency that shifts perspectives, set in an isolated territory swept by winds and waves.

Ann Stouvenel: Why and under what circumstances did you leave?

Grégory Jérôme: It became urgent to take some distance from my daily environment to better understand what has been unfolding in my work for so long and in the reflections that accompany it. There’s nothing like an island, even if one might consider that it’s just another insular space in place of any other. Though there are no walls, the boundaries of space take on a different nature here. Like a school, and indeed like any institution, the space is constantly permeated by external elements, weak or strong signals, like so many birds of good or ill omen. Ultimately, one simply needs to allow oneself to be carried by these ripples, taking the time to understand what they foretell.

AS: What did you find? What encounters did you have?

GJ: Taking a step back and allowing myself a moment of pause in a space shaped and swept by a different kind of movement than the one I am used to forced me into a different kind of attentiveness, calling for other senses, other skills, and testing my adaptability.

The nearly three weeks spent there allowed me to experience time in a unique way, to grasp the particular density it takes on in this deliberate form of confinement—a time whose quality fundamentally depends on the relationships within which it unfolds, whether with humans or non-humans.

Breaking away, taking possession of a place, exploring the surrounding space, trying to discern its rhythms as one might search for a pulse, or perhaps the beating of a heart, allowing a canopy of connections to form that enables one to approach a cohesive whole. If three weeks are not enough—nor even a lifetime—the flows that eventually pass through us make us a part of this place, in the sense that we both contribute and leave a part of ourselves behind; an attachment. Strangeness always paradoxically helps one to rediscover oneself.

AS: How did you move forward with your project?

GJ: Being able to detach myself from the places I usually inhabit allowed me to focus and reflect on my practice, to ask myself the right questions. I managed to write about fifteen pages that represent, in a way, the framework upon which elements of a softer and more flexible consistency—muscular, if you will—should come to attach themselves through ligature and a certain number of articulations. These elements, made of narrated experiences, lived situations, and significant encounters (some of them crucial), form the coordinates of a body of work and a reflection that began in 2001 and continues today.

AS: What did you leave behind—both at home and at the residency?

GJ: I let go of a great and futile agitation to find another one, more raw and undoubtedly more essential. At Ledenez, I left behind tiny particles that settled into the crevices of the wooden planks of the refuge. I allowed myself to be traversed by the networks woven by passing birds, by the spray of the sea. In this way, I leave a little of myself and carry a little of the insular space I’ve departed from.

AS: Was the double isolation—on a peninsula of an island, the solitude, the distance from daily life and the mainland—important, even necessary, in today’s context or not?

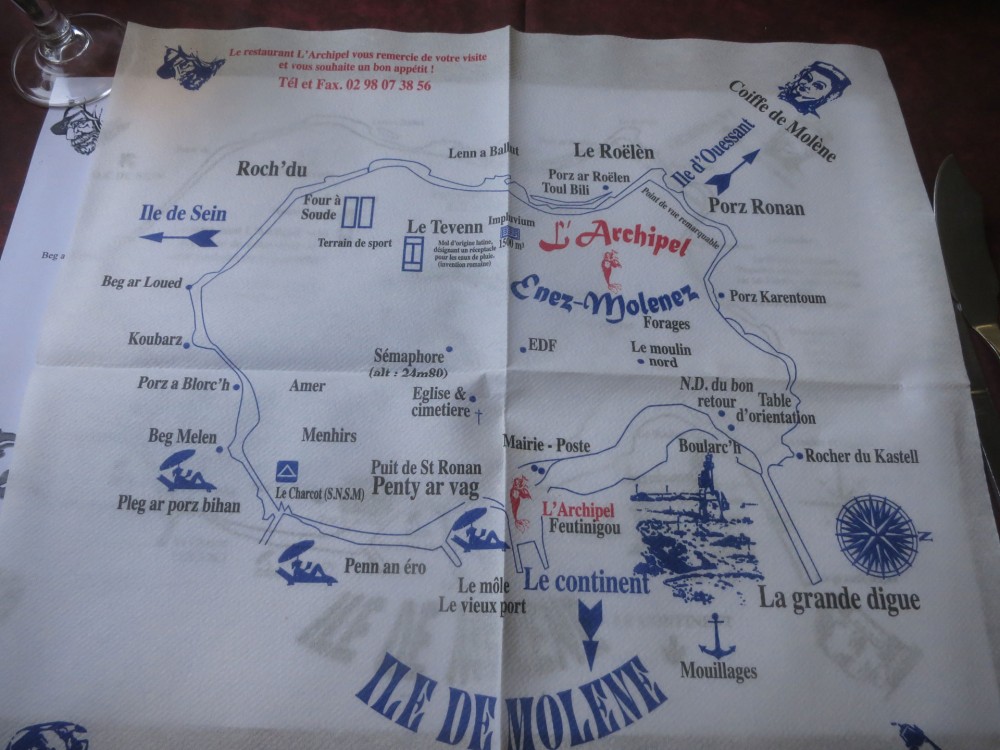

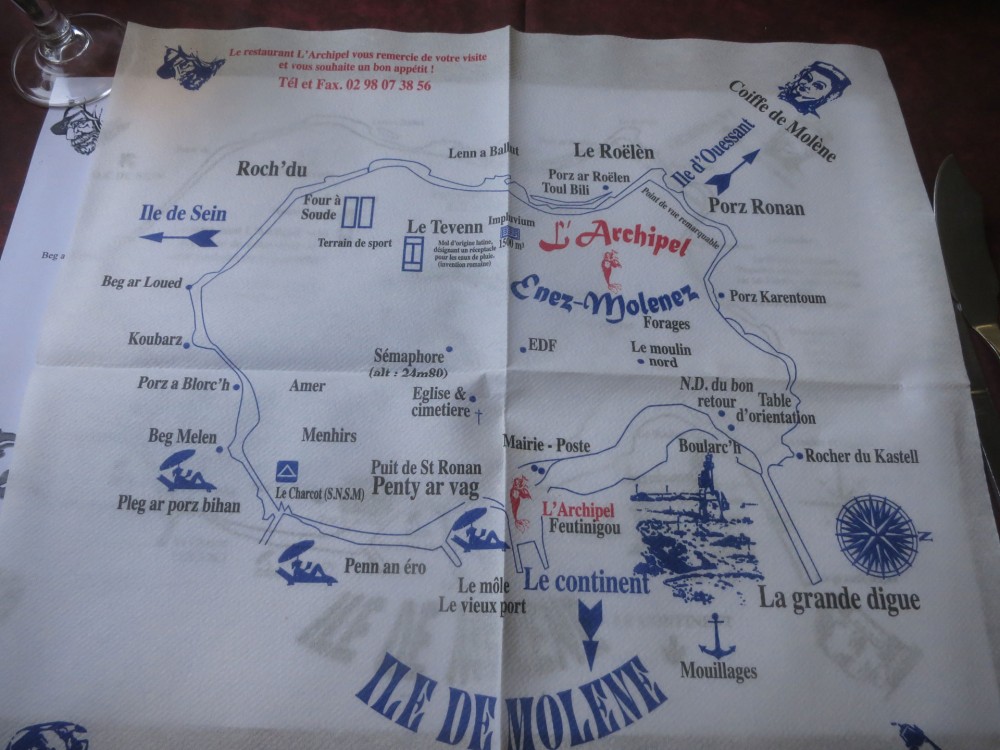

GJ: I wish it for everyone. Each of these small crossings—braving the train and subway strikes, facing the prospect of a storm while boarding the ferry in Brest, disembarking in Molène before finally setting foot on the pebble path that connects Ledenez to Molène—is like climbing a rung that gives us a bit more perspective. I would gladly borrow a phrase from Gaston Rebuffat that perfectly applies to the situation: “The mountaineer is a man who takes his body to where, one day, his eyes have gazed.”