Pauline Delwaulle

Residencie transat #1

A solo residency focused on research and encounters, on the other side of the Atlantic.

Saint-Pierre et Miquelon

Residencie transat #1

A solo residency focused on research and encounters, on the other side of the Atlantic.

After 1 hour and 30 minutes of crossing, I step off the ferry and retrieve my bike, which traveled on the deck of the boat. It’s damp and speckled with salt crystals.

A quick rinse with a hose at the port, as advised by the crew. All the other passengers have left in their pickups. Curious glances are cast toward my bike and its passenger.

I ride through the sleepy village, heading towards the isthmus of Miquelon-Langlade.

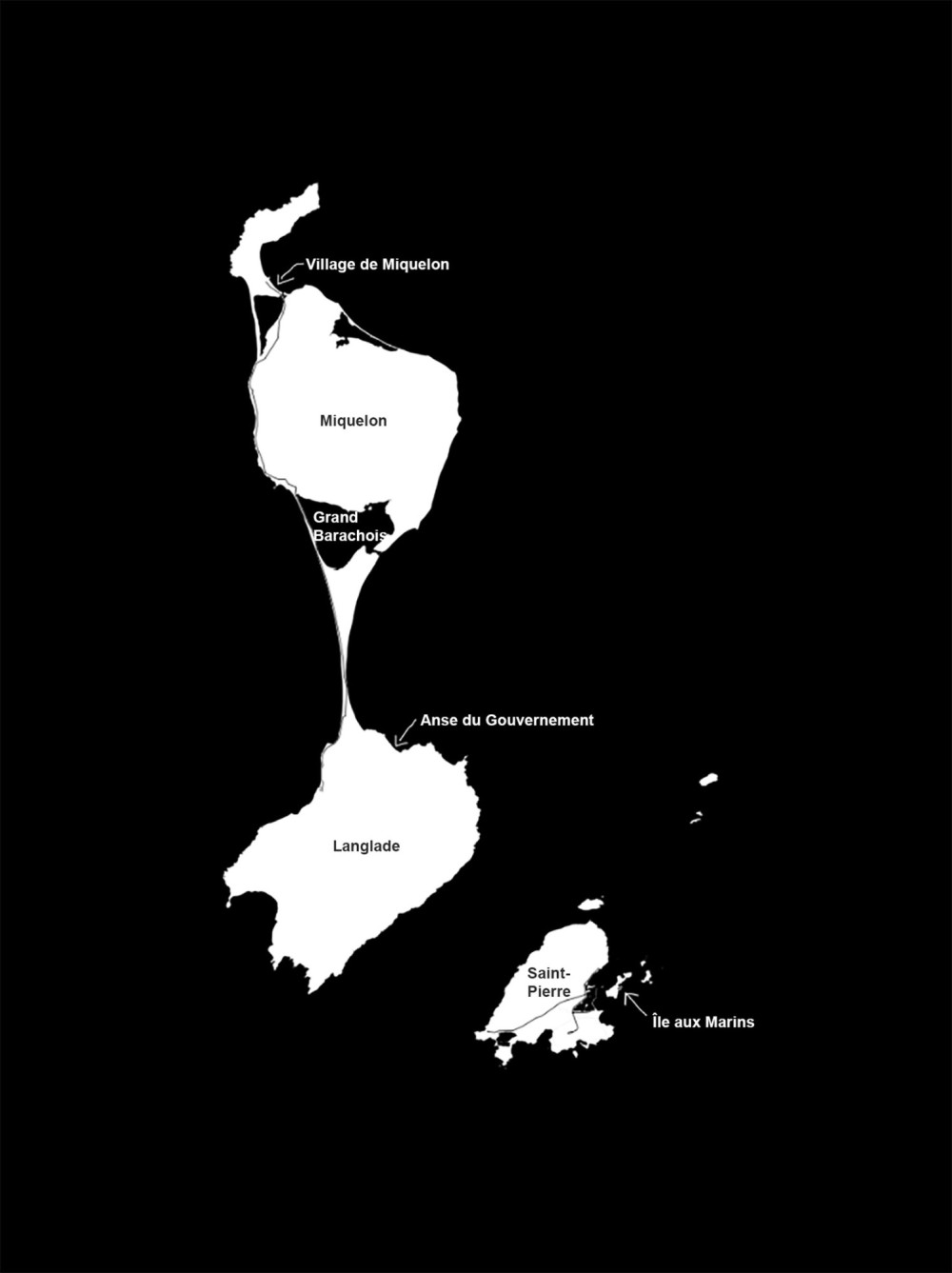

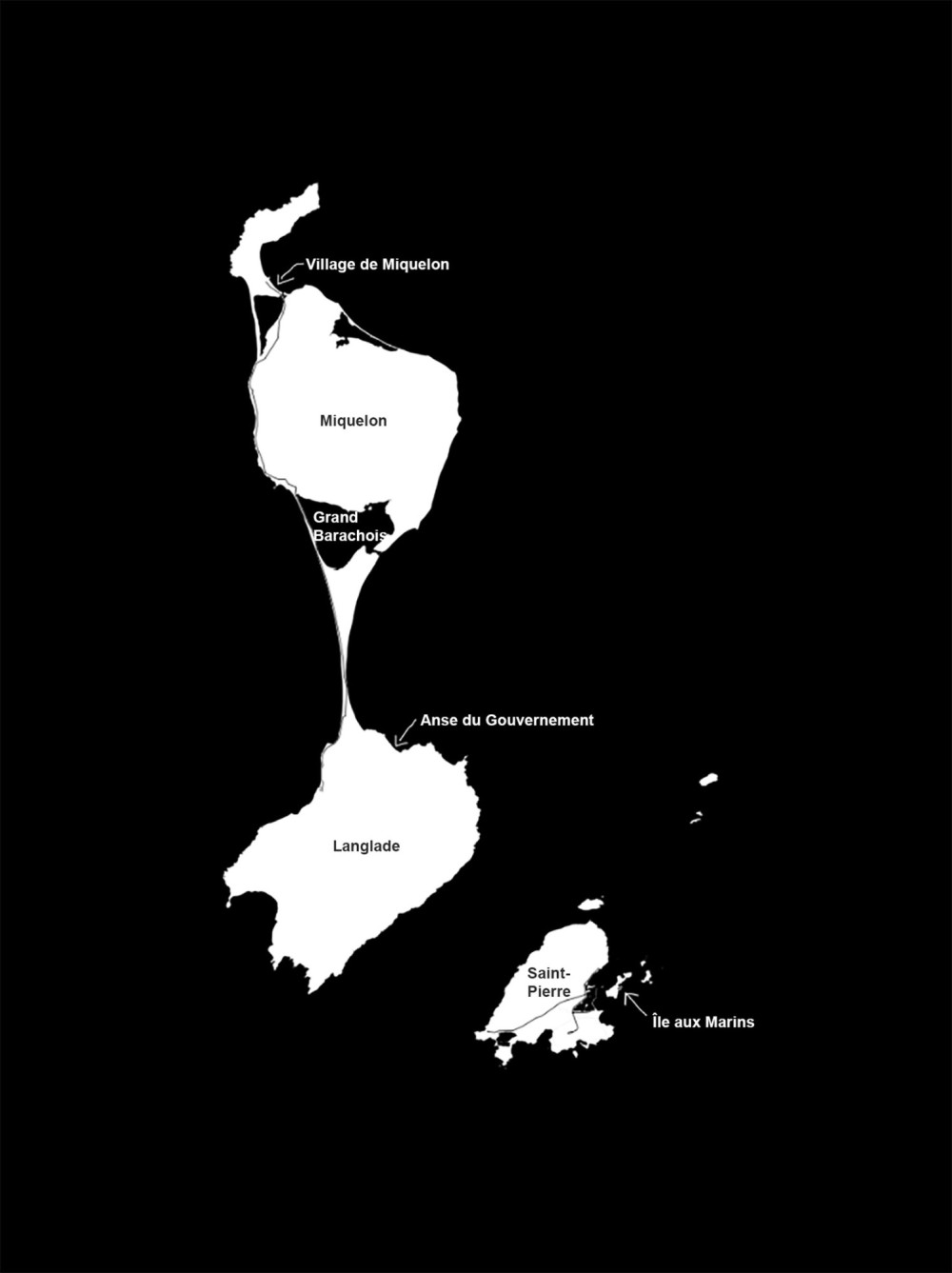

Miquelon-Langlade is an archipelago connected to Saint-Pierre, where I’ve been invited for a residency. My house-studio is on a small island opposite the port of Saint-Pierre, called Île aux Marins. The island has few inhabitants; it’s mostly summer homes without the convenience of running water or easy electricity. Each evening, I walk around the island (about 1 km long) and can see which houses are occupied for the night.

Flags are hoisted by residents when they’re present: the red-footed flag of Île aux Marins, the flag of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and that of their family’s region of origin—Breton, Basque, or Norman. The flagpoles are often adorned on Jeanine and Michou’s house and the lobster fisherman’s home.

In case of trouble, I know I can knock.

During the day, Yannick from the Archipelago Heritage Preservation Association is around. If I have a problem, I search the island for his little orange tractor.

There’s also Filou and Mathieu, the crew of the boat Le Petit Gravier, which shuttles between the island and Saint-Pierre.

In the mornings, if I’m not on the porch with my coffee to greet them as they pass, they honk like a wedding convoy to make sure I come out and wave that all is well.

Thanks to them, I don’t feel isolated.

I pedal south, facing the wind as usual. The return trip will be more pleasant.

I’ve always imagined this archipelago as a piece of chewing gum split into two roughly equal parts, connected by stretchy threads. On the map, at least, that’s how it looks.

I climb the first small hill outside the village, and a big gust of wind stops me dead in my tracks. A pause is needed to better secure my load and reduce wind resistance.

I ride through the moorland, waving to passing pickups. That’s the way here—everyone greets each other, even in the supermarket aisles.

I like this tradition; it makes me feel less like a stranger.

The TV report on Île aux Marins brought me out of anonymity. People no longer ask, “Who are you with?” but now recognize me as “the artist from the blue house on Île aux Marins.” Yet, I’m still a mayoux—a term for someone from mainland France.

I’m no longer anonymous, but I’m still an outsider.

I cross the island of Miquelon, skirting its rounded back from the west.

The humidity gradually fades, in sync with the rising sun.

The mist lifts slightly and merges with the low cloud cover.

Now I can see far.

I search for the purpose of my visit.

The isthmus briefly appears. Like an anamorphosis, it vanishes around the bend.

I turn back to find a better view.

I set the bike down and walk into the heather to take a photo.

I understand what I see because I know the map by heart; I recognize the landscape.

The isthmus, a sedimentary accumulation connecting two lands—a sandbar crossed by a sometimes-paved path—isn’t so easy to spot.

It’s most evident from the air.

The isthmus formed several hundred years ago. On the earliest maps of the archipelago, Miquelon and Langlade were two separate islands.

Sand, carried by ocean and wind, moves and deposits itself slowly over time.

I love the term “sedimentary migration.”

Sandbanks and dunes fatten, stretch, and gradually connect the two islands.

I ride across this ephemeral passage.

The isthmus is slowly eroding. Each year, sections of the road torn away by the ocean have to be rebuilt. The sand is disappearing, and the passage is narrowing.

One day, water will break through, creating a gap in this sandy barrier and separating the two islands again.

The Grand Barachois, a vast lagoon home to diverse species, will vanish too.

The outline of the land here is constantly shifting, which is what draws me.

The landscape changes, and the inhabitants adapt—they have little choice.

Water seeps from all sides: the ocean from the edges, and groundwater from below.

The isthmuses create unique large lagoons on these islands.

These long sandy lines connect various parts of the archipelago.

I’m not satisfied with the framing of my photo; I see the isthmus only because I know it’s there. I try to find a vantage point where I can see the Grand Barachois to the east, the isthmus in the center, and the ocean to the west. The landscape is so flat that the isthmus is indistinguishable from the islands except in a few spots on the plateaus.

I continue south, alternating views of the ocean and the Grand Barachois. I can’t see both at once.

The road switches from one side of the dune to the other.

One moment it’s the ocean, held back by riprap; the next, the calm of a lagoon filled with thousands of birds.

The rocks, imported from Saint-Pierre by barge, attempt to keep the road from washing away. Another kind of sedimentary migration.

On the ocean side, I hear waves crashing against the rocks.

On the Grand Barachois side, I catch the occasional birdcall amid the nearby roar of the waves.

To hear anything, I have to keep my head facing the wind; otherwise, all I hear is the deafening sound of gusts funneling into my ears.

The road’s surface changes again. Repaired a few months ago, it had collapsed over several meters.

The rhyolite rocks, green and red in hue, are neatly aligned, not yet disturbed by the waves.

A white geotextile beneath them helps keep them in place. It looks like a nearly pristine sheet draped over the blocks.

They seem asleep, waiting for autumn storms to wake them.

I switch sides again.

Wooden fences line the dunes covered with marram grass. I’ve always liked these little barriers that seem too flimsy to hold back sand but work well. Here, like elsewhere, sand is corralled to prevent it from escaping too quickly.

On this side, I’m sheltered from the wind.

Arctic terns loudly alert me that the small beach I’m about to stop at is a massive nesting site.

I head south, skirting the unseen ocean.

The isthmus widens; there are no longer dunes, but it’s so broad that the two water bodies can’t fit into the same photo.

I know water is on either side, just out of view.

I ride along a sandy, gravelly path.

Pickups are visible from afar, thanks to the dust clouds trailing behind them.

Peat bogs follow the moorland.

Small houses line the lagoons.

Horses roam freely in the distance.

I pass many people crouched in the dunes and bogs, gathering cloudberries—orange berries whose jam tastes like apricot.

The number of houses increases as the isthmus widens, and I barely hear the ocean anymore.

A pickup honks; I recognize part of the scientific research platform team in the back. Dressed in fishing gear, they’ve been counting brook trout today.

I’ll meet them later at the lobster festival.

I continue towards the end, the hamlet of Anse du Gouvernement.

No one lives year-round in Langlade; like Île aux Marins, it’s all summer homes.

The gravel track turns to sand, and I push my bike into the village.

On the beach by the road, a few brave children play in the water.

The small ferry connecting Saint-Pierre to Langlade is unloading passengers and cargo.

There’s no dock at the hamlet; everything is unloaded via zodiac in multiple trips.

The passengers are already ashore, and now it’s the turn of bags, luggage, dogs, parcels, and bikes.

The zodiac is packed to the brim, the pilot barely visible.

A human chain about fifteen meters long forms on the beach, passing items from hand to hand. The zodiac gradually empties.

Pickups start one by one, disappearing in a cloud of dust.

The beach falls quiet.

I’m lucky today—no rain.

This project was carried out with the support and collaboration of the Mission aux Affaires Culturelles - Ministry of Culture

Supported by the Ministry of Overseas Territories

With the guidance of the DRAC Bretagne - Ministry of Culture

Project realized in partnership with the Sauvegarde du Patrimoine de l’Archipel Association

Our objective is to continue the actions for preserving the built heritage, sites, and maritime areas of the Archipelago, aiming to promote its history for both residents and visitors. The Sauvegarde du Patrimoine de l’Archipel Association is supported by the State (Ministry of Culture) and local authorities (municipalities and the Territorial Collectivity).

Currently, the Association owns six houses: five on Île aux Marins and one in Saint-Pierre, including the entire Morel House.

This classified historical site includes the fisherman’s house with its salt storage, workshop, shop, smokehouse, quay with capstan, and pebble beach. It is undergoing historical restoration managed by the Sauvegarde du Patrimoine de l’Archipel Association with the support of the State.

THANK YOU !

Finis terrae and the artists extend special thanks to:

Martine Briand, Stéphane Claireaux, Esther Derouet, Olivier Lerch, Rosiane de Lizaraga, Henry Masson, Éric Soulier, Yannik Turpin, Marie-Annick Vigneau, the Les Zigotos Association, for their participation, attentiveness, and invaluable support.